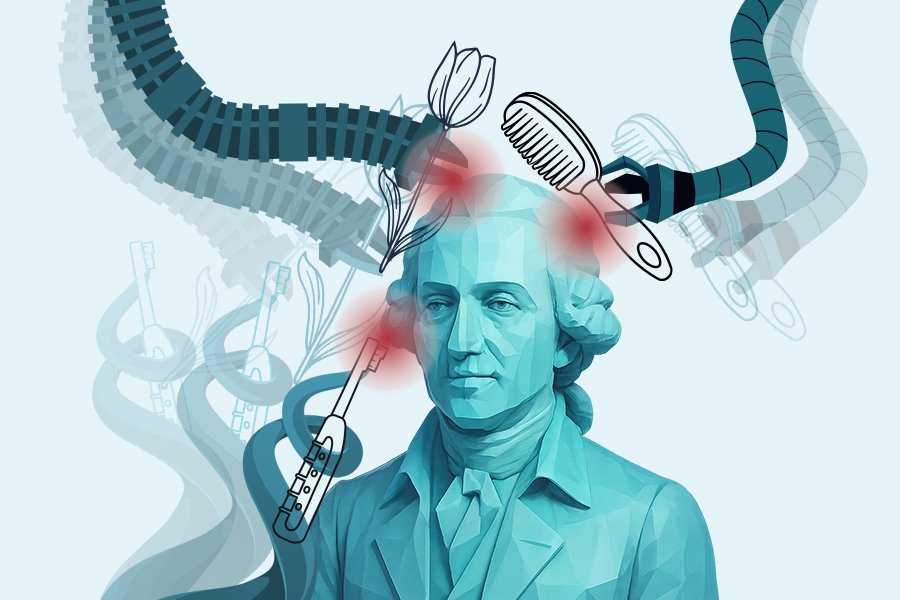

about the Small-World Experiment, conducted by Stanley Milgram in the 1960’s. He devised an experiment by which a letter was given to a volunteer person in the United States, with the instruction to forward the letter to their personal contact most likely to know another person – the target – in the same country. In turn, the person receiving the letter would be asked to forward the letter again until the target person was reached. Although most of the letters never reached the target person, among those that did (survivorship bias at play here!), the average number of hops was around 6. The “six degrees of separation” has become a cultural reference to the tight interconnectivity of society.

I am still amazed by the thought that people with ~102 contacts manage to connect with a random person in a network of ~108 people, through a few hops.

How is that possible? Heuristics.

Let’s assume I am asked to send a letter to a target person in Finland1.

Unfortunately, I don’t have any contacts in Finland. On the other hand, I know someone who lived in Sweden for many years. Perhaps she knows people in Finland. If not, she probably still has contacts in Sweden, which is a neighboring country. She is my best bet to get closer to the target person. The point is, although I do not know the topology of the social network beyond my own personal contacts, I can use rules of thumb to forward the letter in the right direction.

If we adopt the point of view of the network’s nodes (the humans involved in the experiment), their available actions are to forward the message (the letter) to one of their outgoing edges (personal contacts). This problem of transmitting the message in the right direction offers an opportunity to have fun with machine learning!

Nodes do not perceive the whole network topology. We can set up an environment that rewards them for routing the message along the shortest known path, while encouraging them to explore sub-optimal candidate paths. That sounds like a great use case for reinforcement learning, don’t you think?

For those interested in running the code, you can reach the repo here.

The Problem

We’ll be given a directed graph where edges between nodes are sparse, meaning the average number of outgoing edges from a node is significantly smaller than the number of nodes. Furthermore, the edges will have an associated cost. This additional feature generalizes the case of the Small-World Experiment, where each hop of the letter counted for a cost of 1.

The problem we’ll consider is to design a reinforcement learning algorithm that finds a path from an arbitrary start node to an arbitrary target node in a sparse directed graph, with a cost as low as possible, if such a path exists. Deterministic solutions exist for this problem. For example, Dijkstra’s algorithm finds the shortest path from a start node to all the other nodes in a directed graph. This will be useful to evaluate the results of our reinforcement learning algorithm, which is not guaranteed to find the optimal solution.

Q-Learning

Q-Learning is a reinforcement learning technique where an agent maintains a table of state-action pairs, associated with the expected discounted cumulative reward – the quality, hence the Q-Learning. Through iterative experiments, the table is updated until a stopping criterion is met. After training, the agent can choose the action (the column of the Q-matrix) corresponding to the maximal quality, for a given state (the row of the Q-matrix).

The update rule, given a trial action aj, resulting in the transition from state si to state sk, a reward r, and a best estimate of the quality of the next state sk, is:

\[ Q(i, j) \leftarrow (1 – \alpha) Q(i, j) + \alpha \left( r + \gamma \max_{l} Q(k, l) \right) \]

Equation 1: The update rule for Q-Learning.

In equation 1:

αis the learning rate, controlling how fast new results will erase old quality estimates.- γ is the discount factor, controlling how much future rewards compare with immediate rewards.

Qis the quality matrix. The row indexiis the index of the origin state, and the column indexjis the index of the selected action.

In short, equation 1 states that the quality of (state, action) should be partly updated with a new quality value, made of the sum of the immediate reward and the discounted estimate of the next state’s maximum quality over possible actions.

For our problem statement, a possible formulation for the state would be the pair (current node, target node), and the set of actions would be the set of nodes. The state set would then contain N2 values, and the action set would contain N values, where N is the number of nodes. However, because the graph is sparse, a given origin node has only a small subset of nodes as outgoing edges. This formulation would result in a Q-matrix where the large majority of the N3 entries are never visited, consuming memory needlessly.

Distributed agents

A better use of resources is to distribute the agents. Each node can be thought of as an agent. The agent’s state is the target node, hence its Q-matrix has N rows and Nout columns (the number of outgoing edges for this specific node). With N agents, the total number of matrix entries is N2Nout, which is lower than N3.

To summarize:

- We’ll be training

Nagents, one for each node in the graph. - Each agent will learn a

Q-matrix of dimensions[N x Nout]. The number of outgoing edges (Nout) can vary from one node to another. For a sparsely connected graph,Nout<< N. - The row indices of the

Q-matrix correspond to the state of the agent, i.e., the target node. - The column indices of the

Q-matrix correspond to the outgoing edge selected by an agent to route a message toward the target node. Q[i, j]represents a node’s estimate of the quality of forwarding the message to itsjth outgoing edge, given the target node isi.- When a node receives a message, it will include the target node. Since the sender of the previous message is not needed to determine the routing of the next message, it will not be included in the latter.

Code

The core class, the node, will be named QNode.

class QNode:

def __init__(self, number_of_nodes=0, connectivity_average=0, connectivity_std_dev=0, Q_arr=None, neighbor_nodes=None,

state_dict=None):

if state_dict is not None:

self.Q = state_dict['Q']

self.number_of_nodes = state_dict['number_of_nodes']

self.neighbor_nodes = state_dict['neighbor_nodes']

else: # state_dict is None

if Q_arr is None:

self.number_of_nodes = number_of_nodes

number_of_neighbors = connectivity_average + connectivity_std_dev * np.random.randn()

number_of_neighbors = round(number_of_neighbors)

number_of_neighbors = max(number_of_neighbors, 2) # At least two out-connections

number_of_neighbors = min(number_of_neighbors, self.number_of_nodes) # Not more than N connections

self.neighbor_nodes = random.sample(range(self.number_of_nodes), number_of_neighbors) # [1, 4, 5, ...]

self.Q = np.zeros((self.number_of_nodes, number_of_neighbors)) # Optimistic initialization: all rewards will be negative

# q = self.Q[state, action]: state = target node; action = chosen neighbor node (converted to column index) to route the message to

else: # state_dict is None and Q_arr is not None

self.Q = Q_arr

self.number_of_nodes = self.Q.shape[0]

self.neighbor_nodes = neighbor_nodesThe class QNode has three fields: the number of nodes in the graph, the list of outgoing edges, and the Q-matrix. The Q-matrix is initialized with zeros. The rewards received from the environment will be the negative of the edge costs. Hence, the quality values will all be negative. For this reason, initializing with zeros is an optimistic initialization.

When a message reaches a QNode object, it selects one of its outgoing edges through the epsilon-greedy algorithm. If ε is small, the epsilon-greedy algorithm selects most of the time the outgoing edge with the highest Q-value. Once in a while, it will select an outgoing edge randomly:

def epsilon_greedy(self, target_node, epsilon):

rdm_nbr = random.random()

if rdm_nbr < epsilon: # Random choice

random_choice = random.choice(self.neighbor_nodes)

return random_choice

else: # Greedy choice

neighbor_columns = np.where(self.Q[target_node, :] == self.Q[target_node, :].max())[0] # [1, 4, 5]

neighbor_column = random.choice(neighbor_columns)

neighbor_node = self.neighbor_node(neighbor_column)

return neighbor_nodeThe other class is the graph, called QGraph.

class QGraph:

def __init__(self, number_of_nodes=10, connectivity_average=3, connectivity_std_dev=0, cost_range=[0.0, 1.0],

maximum_hops=100, maximum_hops_penalty=1.0):

self.number_of_nodes = number_of_nodes

self.connectivity_average = connectivity_average

self.connectivity_std_dev = connectivity_std_dev

self.cost_range = cost_range

self.maximum_hops = maximum_hops

self.maximum_hops_penalty = maximum_hops_penalty

self.QNodes = []

for node in range(self.number_of_nodes):

self.QNodes.append(QNode(self.number_of_nodes, self.connectivity_average, self.connectivity_std_dev))

self.cost_arr = cost_range[0] + (cost_range[1] - cost_range[0]) * np.random.random((self.number_of_nodes, self.number_of_nodes))

Its main fields are the list of nodes and the array of edge costs. Notice that the actual edges are part of the QNode class, as a list of outgoing nodes.

When we want to generate a path from a start node to a target node, we call the QGraph.trajectory() method, which calls the QNode.epsilon_greedy() method:

def trajectory(self, start_node, target_node, epsilon):

visited_nodes = [start_node]

costs = []

if start_node == target_node:

return visited_nodes, costs

current_node = start_node

while len(visited_nodes) < self.maximum_hops + 1:

next_node = self.QNodes[current_node].epsilon_greedy(target_node, epsilon)

cost = float(self.cost_arr[current_node, next_node])

visited_nodes.append(next_node)

costs.append(cost)

current_node = next_node

if current_node == target_node:

return visited_nodes, costs

# We reached the maximum number of hops

return visited_nodes, costsThe trajectory() method returns the list of visited nodes along the path and the list of costs associated with the edges that were used.

The last missing piece is the update rule of equation 1, implemented by the QGraph.update_Q() method:

def update_Q(self, start_node, neighbor_node, alpha, gamma, target_node):

cost = self.cost_arr[start_node, neighbor_node]

reward = -cost

# Q_orig(target, dest) <- (1 - alpha) Q_orig(target, dest) + alpha * ( r + gamma * max_neigh' Q_dest(target, neigh') )

Q_orig_target_dest = self.QNodes[start_node].Q[target_node, self.QNodes[start_node].neighbor_column(neighbor_node)]

max_neigh_Q_dest_target_neigh = np.max(self.QNodes[neighbor_node].Q[target_node, :])

updated_Q = (1 - alpha) * Q_orig_target_dest + alpha * (reward + gamma * max_neigh_Q_dest_target_neigh)

self.QNodes[start_node].Q[target_node, self.QNodes[start_node].neighbor_column(neighbor_node)] = updated_QTo train our agents, we iteratively loop through the pairs of (start_node, target_node) with an inner loop over the neighbor nodes of start_node, and we call update_Q().

Experiments and Results

Let’s start with a simple graph of 12 nodes, with directed weighted edges.

We can observe from Figure 1 that the only incoming node to Node-1 is Node-7, and the only incoming node to Node-7 is Node-1. Therefore, no other node besides these two can reach Node-1 and Node-7. When another node is tasked with sending a message to Node-1 or Node-7, the message will bounce around the graph until the maximum number of hops is reached. We expect to see large negative Q-values in these cases.

When we train our graph, we get statistics about the cost and the number of hops as a function of the epoch, as in Figure 2:

After training, this is the Q-matrix for Node-4:

The trajectory from Node-4 to, say, Node-11, can be obtained by calling the trajectory() method, setting epsilon=0 for the greedy deterministic solution: [4, 3, 5, 11] for a total undiscounted cost of 0.9 + 0.9 + 0.3 = 2.1. The Dijkstra algorithm returns the same path.

In some rare cases, the optimal path was not found. For example, to go from Node-6 to Node-9, a specific instance of the trained Q-graph returned [6, 11, 0, 4, 10, 2, 9] for a total undiscounted cost of 3.5, while the Dijkstra algorithm returned [6, 0, 4, 10, 2, 9] for a total undiscounted cost of 3.4. As we stated before, this is expected from an iterative algorithm

Conclusion

We formulated the Small-World Experiment as a problem of finding the path with minimum cost between any pair of nodes in a sparse directed graph with weighted edges. We implemented the nodes as Q-Learning agents, who learn through the update rule to take the least costly action, given a target node.

With a simple graph, we showed that the training settled to a solution close to the optimal one.

Thank you for your time, and feel free to experiment with the code. If you have ideas for fun applications for Q-Learning, please let me know!

1 OK, I’m going beyond the original Small-World Experiment, which should be called the Small-Country Experiment.

References

Reinforcement Learning, Richard S. Sutton, Andrew G. Barto, MIT Press, 1998