article in my data visualization series. See the previous article: “Data Visualization Explained: What It Is and Why It Matters.”

So, now you’ve learned the foundational idea of what underlies data visualization and why it is an essential component of the data science ecosystem. (If you are not familiar with this, be sure to check out the article linked above.)

As we discussed in the previous article, the core idea of data visualization is finding an effective way to represent data of various types in a visual manner.

The key underlying concept which makes this representation work is known as a visual encoding channel. A visual encoding channel is effectively the means through which numerical, textual, or some other form of data is translated into a visual mark. The best way to think of it is as a visual feature corresponding to all or part of your data. Effective data visualizations often use multiple visual encoding channels for different aspects of the data.

In this second article, we’ll dive into the details of visual encoding channels and gain some practice breaking down a complex visualization into its component parts. This will prepare you for designing your own visualizations in the near future.

Introduction to Visual Variables

In his 1967 work, The Semiology of Graphics, French cartographer Jacques Bertin outlined seven “retinal” variables, named as such because the human eye’s retina is sensitive to them [1]:

- Position (such as the coordinates on a graph)

- Size

- Shape

- Color hue

- Color value (lightness to darkness)

- Orientation

- Texture

Although Bertin published his work decades ago, his visual variables remain an excellent guideline for modern data visualization design. In the early phases of developing a visualization, it is good practice to review the visual variables available and determine which ones to use for specific variables in the data.

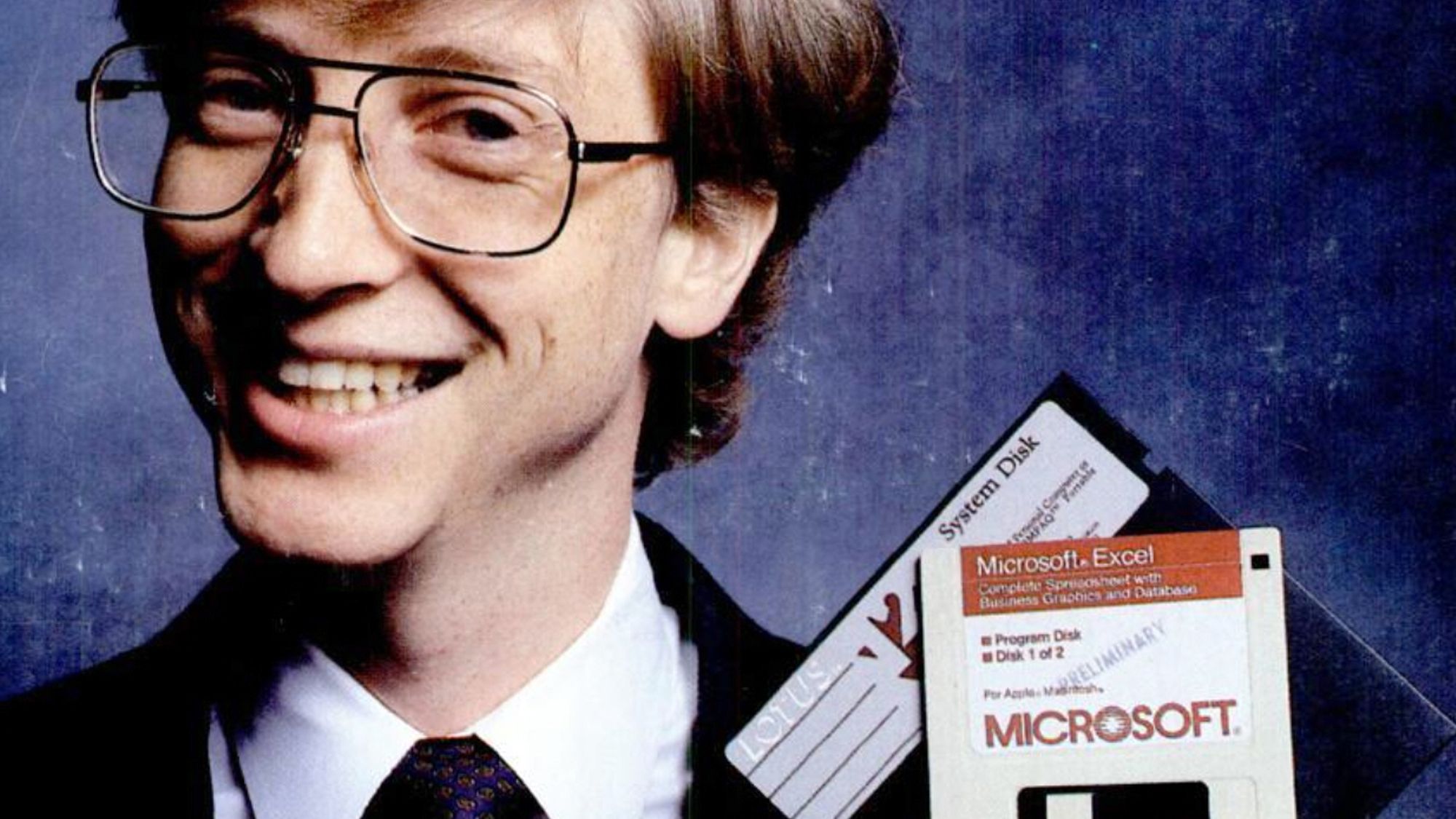

This can be a confusing concept and is more easily understood with an example. The graphic below, often considered a masterful application of visualization, was designed and drawn by Charles Minard. It depicts Napoleon’s failed invasion of Russia.

This is a simplified and translated version of the map to ease readability; for the original, see here [2].

What different visual variables are being used in the graphic above? (Hint: There are quite a few.) As an exercise, get out a pen and paper and try to determine this yourself. We’ll walk through it in detail in a bit.

Maximizing Effectiveness of Visual Variables

The best visual variable to use for a specific visualization depends on the data. Here, we will look at three different types of data:

- Quantitative: Numerical data with a natural ordering that is suitable for mathematical operations (i.e., it makes sense to add/subtract/multiply/divide individual data values). For example, salary and age are quantitative variables.

- Ordinal: Categorical data (i.e., non-numerical data which can take on a fixed number of values) that still has a natural ordering. If you have ever taken a survey with answer choices such as “Strongly Agree,” “Agree,” “Neutral,” “Disagree,” and “Strongly Disagree,” then you have seen ordinal data in action. While mathematical operations on this data don’t make sense, various values can still be ordered from “best” to “worst,” so to speak.

- This also includes variables that may have an order without technically being “ranked,” such as traffic light patterns.

- Nominal: Categorical data which has no natural ordering. A great example of this is color. While it is possible to distinguish between different colors, they have no natural sequence. (This also explains why color is an excellent visual encoding for nominal variables in general, as we’ll see below!)

Important: Just because a variable is a number does not automatically make it quantitative. For example, zip codes are numbers, but they have no natural ordering, nor can one perform mathematical operations on them. Thus, zip code is a nominal variable.

The following table, a variation of one designed by visualization experts Jock D. Mackinlay and Stuart Card, outlines the effectiveness of different visual variables depending on the type of data [2]:

| Quantitative | Ordinal | Nominal |

| Position | Position | Position |

| Length | Density | Hue |

| Angle | Saturation | Texture |

| Slope | Hue | Connection |

| Area | Texture | Containment |

| Volume | Connection | Density |

| Density | Containment | Saturation |

| Saturation | Length | Shape |

| Hue | Angle | Length |

| Slope | Angle | |

| Area | Slope | |

| Volume | Area | |

| Volume |

A few key points about these rankings:

- Position is the best option for all variable types. For example, a bar graph with names on the x-axis and blood pressure on the y-axis uses position for both a nominal variable and quantitative variable, respectively.

- After position, desirability changes for each variable type. This is important to know because if you are graphing several variables, you’ll eventually have to use something other than position because it’s already being used (usually on a 2-D graph with two axes).

- Length is an extension of position, but especially useful for quantitative comparisons.

- Density and saturation are great for ordinal variables, as your viewers don’t need to determine exact values—they just need to see the rankings.

- Hue and shape work well for nominal variables, making it easy to see categorical differences.

- Some options are entirely crossed out because they simply wouldn’t make sense. For example, shape is not a possible encoding choice for quantitative or ordinal variables, because there would be no way to compare quantities or understand orders.

Now, let’s walk through an example of how to break down visual encoding channels in detail.

Minard’s Map: Breaking Down the Variables

Let’s look at Minard’s map of Napoleon’s invasion together. Here it is again for convenience. This example is taken from Edward Tufte’s famous visualization book, The Visual Display of Quantitative Information [3].

A careful study of this map shows Charles Minard’s mastery of visual encoding channels as nothing short of brilliant. His visualization displays six different variables:

- Geographic Location (Quantitative): Position is used to display the location of Napoleon’s army on a 2-D surface (so this is technically two variables). The invasion began on the left side of the map, on the Polish-Russian border. We can also see how at times, parts of the army branch off to different locations as part of Napoleon’s strategy.

- Geographic Location (Quantitative): See above.

- Time (Quantitative): Looking closely, we can see that various points in time are listed on the chart’s x-axis at the bottom of the visualization. Again, the position is used to display this variable.

- Temperature (Quantitative): Temperature is plotted in relation to time on the chart underneath the map. Position is used yet again, this time on the y-axis.

- Number of Troops Remaining in Army (Quantitative): The width of the shape moving across the map represents the number of troops in Napoleon’s army. It is clear that as the invasion progressed, Napoleon’s army became smaller and smaller. They eventually returned to Poland with only 10,000 living soldiers out of an initial 422,000.

- Direction of the Army’s Movement (Nominal): Color is used to depict the direction in which the army moves at various positions. The beige/tan color (white in the simplified image we have above) indicates the army’s movement toward Moscow, and the black color indicates its retreat back into Poland.

In his book [3], Tufte refers to Minard’s map as possibly “the best statistical graphic ever drawn.” Studying it can inspire us to devise clever ways to encode our own data visually.

Final Thoughts and Looking Forward

With this second article, you’ve learned the foundational idea behind visualization design: visual encoding channels. As you reflect on what you’ve learned, keep the following key points in mind:

- The choice of visual encoding channel can often make or break a visualization. You might have a beautifully designed graphic, but if the visual encoding channels are hard to interpret, your viewers won’t know what you’re trying to say.

- Position reigns supreme for all variable types, but there is limited space in a 2-D environment. As such, think carefully about which variables you display with position; they’ll often be the most important ones.

- Try out different designs! There is no “one” perfect solution. Rather, you must revise and reiterate until you reach a satisfactory point.

In the next article, we’ll talk about important tips for visualization design and how techniques have evolved and expanded over the last several decades. Until then.

References

[1] Semiology of Graphics, Jacques Bertin (translated by J. Ronald Eastman)

[2] https://ageofrevolution.org/200-object/flow-map-of-napoleons-invasion-of-russia/

[2] Readings in information visualization: using vision to think (Card, Mackinlay, and Shneiderman)

[3] The Visual Display of Quantitative Information, Edward Tufte